An Ethical Philosophy

balance, proportion and symmetry

By Yannis Andricopoulos

In a way, it's all Prince Charles' fault. Back in 1982, a couple of years before Atsitsa raised the flag of holism, he gave a speech in which he criticised modern medicine. By concentrating on smaller and smaller fragments of the body, medicine, he said, has lost sight of the patient as a whole human being. I can vividly recall my instant reaction to it - fascination. The rest of Charles' speech did not enamour me – Paracelsus, the sixteenth century alchemist whom the Prince quoted extensively in support of his point, is not my cup of tea.

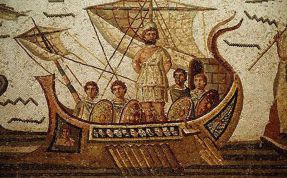

But Charles' lecture reminded me of Hippocrates, the father of medicine, who would not treat a symptom without a full examination of the patient's whole condition, which included even the political system of the city-state. This was not, however, just Hippocrates. The entire Greek culture was based on the same holistic premises, which, as my classical education had left embarrassing gaps, I proceeded to explore anew. The exercise was rewarding. The holistic concept that unfolded was one in which unity enhanced diversity, purpose underpinned freedom, and wholeness strengthened individuality. The whole for the Greeks was more than the sum of its parts.

But Charles' lecture reminded me of Hippocrates, the father of medicine, who would not treat a symptom without a full examination of the patient's whole condition, which included even the political system of the city-state. This was not, however, just Hippocrates. The entire Greek culture was based on the same holistic premises, which, as my classical education had left embarrassing gaps, I proceeded to explore anew. The exercise was rewarding. The holistic concept that unfolded was one in which unity enhanced diversity, purpose underpinned freedom, and wholeness strengthened individuality. The whole for the Greeks was more than the sum of its parts.

This whole, including both the animate and the inanimate world, was a living entity possessing something like a rational cosmic soul which defied definition. This force was not God. It was, instead, the energy that nurtures the seed's transformation into a tree, and which, whatever the Gods might wish, would not allow the river to run back to its source. This energy, which the Greeks called Necessity, permeated the existence of both nature and humanity, and encompassed everything to which man's life was inseparably linked including the individual's own consciousness. It was what kept cosmos together as an orderly and beautiful arrangement. It did also lead to the identification of the individual with everything that is.

Physical reality, sensory perception and mental activity, blending with one another, were, thus, One, the "thing itself" which belonged as much to the world as to the individual. The humans had their place in it as much as it had its place in them. This is, incidentally, what distinguishes the Greek religious thinking from religions which turned the humans into the ‘slaves’ of the ‘Lord’. Considering that Necessity had to be understood rather than worshipped, this is also what gave birth to rationalism. But for the Greeks, rationalism was inseparable from morality. Necessity needed only the certainty that no element of the whole would be dominated by another or eliminated for good. The image is, perhaps, given by the four seasons of the year. They battle with each other, but eventually each one of them makes way for the other. Strife within the whole never ends as no party to it either can, or should be able to, dominate or obliterate its opposition. To do so would disturb the delicate balance of the whole and offend some sort of eternal order which has given everything its place. It would in this sense be hubris, and hubris was bound to be punished in what Solon, the Athenian statesman, called the ‘Court of Time’.

Physical reality, sensory perception and mental activity, blending with one another, were, thus, One, the "thing itself" which belonged as much to the world as to the individual. The humans had their place in it as much as it had its place in them. This is, incidentally, what distinguishes the Greek religious thinking from religions which turned the humans into the ‘slaves’ of the ‘Lord’. Considering that Necessity had to be understood rather than worshipped, this is also what gave birth to rationalism. But for the Greeks, rationalism was inseparable from morality. Necessity needed only the certainty that no element of the whole would be dominated by another or eliminated for good. The image is, perhaps, given by the four seasons of the year. They battle with each other, but eventually each one of them makes way for the other. Strife within the whole never ends as no party to it either can, or should be able to, dominate or obliterate its opposition. To do so would disturb the delicate balance of the whole and offend some sort of eternal order which has given everything its place. It would in this sense be hubris, and hubris was bound to be punished in what Solon, the Athenian statesman, called the ‘Court of Time’.

The concept of holism was, thus, inevitably linked to an ethicality to which both the humans and their senior brothers, the Gods, had no choice but to adhere strictly. This ethicality was rooted in Justice, i.e., in Nature's Justice which acknowledges limits and interdependencies that transcend us all, nurtures no hierarchies and despotic institutions, and has no concept of a ‘natural order’ on whose back inexorable social and political ‘laws’ were subsequently built. Brought into the human realm, this moral principle became the ethical philosophy which called for self-imposed limits, ensured that democracy is a political system blessed by Nature, and gave birth to natural rights, the rights of man or what we call in our days human rights.

The whole which the Greeks honoured did not, of course, include the slaves and the women. Even so, the sense of morality emanating from their commitment to Justice is so breathtaking that it can be held as the ideal even in our days. Morality, after all, is not related to sexuality, and Justice is not about courts and prisons. It is about fairness in our dealings with everything – people, trade, cities, trees, forests and animals, the world, the future generations. In it is summed up the whole of virtue.

The ‘Other’, whether the ‘Other’ is Palestinians, gays, ethnic minorities, the environment or Africa is not an objectified entity external to ourselves, i.e. something to step on to increase ‘our’ wealth and power. Having an intrinsic value, it is, instead, an end in itself which needs to be acknowledged, respected and protected. Abuses at its expense is hubris, an offence against the eternal moral order, that the whole will only live to regret.

The ‘Other’, whether the ‘Other’ is Palestinians, gays, ethnic minorities, the environment or Africa is not an objectified entity external to ourselves, i.e. something to step on to increase ‘our’ wealth and power. Having an intrinsic value, it is, instead, an end in itself which needs to be acknowledged, respected and protected. Abuses at its expense is hubris, an offence against the eternal moral order, that the whole will only live to regret.

It follows that fairness is a condition in dealing with ourselves, too, honouring all its constituent parts- mind, body and spirit. The ‘just man’ who has bound these elements into a disciplined and harmonious whole, Plato said, will be ready to lead an emotionally, intellectually, physically, aesthetically and morally rewarding life. For the Greeks, this meant excellence in all fields. Hence in their vocabulary physical, moral and intellectual excellence was all described by the single word arete. The goal was balance, proportion and symmetry, a life ‘beautiful and honourable’.

The concept is aesthetic, yet it required not only the beauty of the form, but also the beauty of the noble soul. Kalos k'agathos, a good man, was for the Greeks he who excelled, not as a scientist, a businessman or an athlete, but in life itself. The term denotes personal qualities embracing the whole of a man's existence and not exchangeable for other goods such as wealth.

Holism in this sense has, however, disappeared into the mists of history. Christianity abandoned life on earth, and together with it the Greek holistic thinking, for the pleasures of the afterlife guaranteed by the purity of the soul. The mind was dismissed, Reason was rejected, the body was denied and morality was identified with the denial of the flesh.

Capitalism subsequently rediscovered ‘Reason’ but as a weapon in its battle to turn everything into a means to an end which has always been associated with profit. In its Cartesian world, the only important part of ourselves is the mind- the rest, i.e. the body and the soul, are burdens we have no choice but to carry. In opposition to it, the Romantics rediscovered holism but as a totalitarian philosophy at the service of what Jean-Jacques Rousseau called the ‘general will’, and the New Age, like the Gnostics in the past, saw it again in metaphysical terms.

Capitalism subsequently rediscovered ‘Reason’ but as a weapon in its battle to turn everything into a means to an end which has always been associated with profit. In its Cartesian world, the only important part of ourselves is the mind- the rest, i.e. the body and the soul, are burdens we have no choice but to carry. In opposition to it, the Romantics rediscovered holism but as a totalitarian philosophy at the service of what Jean-Jacques Rousseau called the ‘general will’, and the New Age, like the Gnostics in the past, saw it again in metaphysical terms.

Distorted, misinterpreted or abused, holism has been deprived of its essence, detached from its ethical basis and rendered as meaningless as the remarks uttered by the spirits of the dead when we summon them to our presence. This is so even when lip service is paid to holism, when for example the fight against terrorism is linked to a new and fair world order which looks only like the negative of a dream. Indeed, holism means nothing to the free market which is not interested in Justice but in wealth creation, has not set as its aim the happiness of the individual – for what matters is only his or her efficiency as a worker – and cares not about the well-being of the community, but its spending power.

The Greek holistic thought welded together Reason and morality, intellect and feeling, body and spirit, inner and outer, culture and nature, science and intuition, individuality and the public realm. As parts of the whole, whether the whole was the planet, civilisation or the individual, they all had an intrinsic value, a purpose determined by their very existence, and an inalienable right to be. Skyros is attached to this ethical understanding of holism like a sunflower to the sun.